Political Correctness Wanted Dead or Alive: A Rhetorical Witch-Hunt in the US, Russia, and Europe

Guest blogger Dr. Anna Szilagyi describes how politicians including Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump portray the term “political correctness” as an attack on ordinary people. Like the Dangerous Speech analytical framework, Szilagyi‘s analysis illustrates the rhetorical tools that leaders use to reframe language and paint themselves as valiantly protecting their people against a threat.

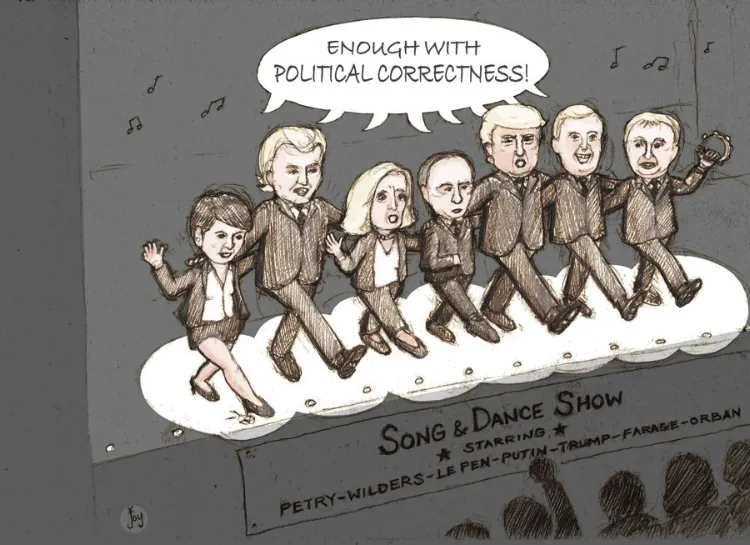

Not long ago, political correctness, or PC, stood for an ideal of fairness and open-mindedness. Yet today, it is a widely bashed catchphrase, with politicians gaining popularity worldwide by destroying the “rosy image” of PC. The list includes US President-elect Donald Trump, Russian President Vladimir Putin, and leaders of populist radical right parties in European countries, among them France, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, and the UK.

In theory, political correctness simply functions as a neutral, descriptive reference to the principle of avoiding utterances and actions that can marginalize or offend certain groups of people. However, because it includes the word “correctness,” PC can also be used and perceived as a normative expression. The noun “correctness” connotes approval and radiates authority. It indicates, with an imperative tone, that something should be done in a particular way. In this regard, the term political correctness can evoke in people the feeling of being talked down to and even subordinated.

Politicians who aim to discredit the notion of PC point to its moralistic connotations. Implicitly endorsing traditional social conventions and hierarchies, they commonly portray political correctness as a norm that is imposed on society in a top-down manner. Constructing political correctness as an arbitrarily enforced, biased agenda, anti-PC politicians adopt common discursive strategies across the globe in their attempt to undermine and discredit PC. As this brief summary highlights, their anti-PC rhetoric is also part of an effort to push their own agenda.

EXTRAVAGANCE VS NECESSITIES

In the recent American presidential campaign, Donald Trump consistently described PC through metaphors that refer to the “cost” of things: “We just can’t afford anymore to be so politically correct.” The metaphor of “affordability” allowed Trump to talk about political correctness as if it were something expensive (e.g. a high-priced car, a designer bag). This was a way of creating the impression that political correctness is a non-essential extravagance.

Politicians who portray PC as something superfluous and unnecessary also evoke anti-elite sentiments. Trump’s metaphor of “affordability” implied, for instance, that political correctness is a privilege of a tiny group of affluent people. Additionally, by portraying PC as a luxury, speakers can create the impression that they represent the many and not the privileged few. Trump, a billionaire businessman, also introduced himself as an average American who cannot “afford” PC: “I don’t frankly have time for total political correctness. And to be honest with you, this country doesn’t have time either.”

ELITE CONCERN VS ACTUAL PROBLEMS

PC is associated with the elite by the European populist radical right parties as well. At a joint press conference in 2016, the French National Front President Marine Le Pen, the Dutch Freedom Party leader Geert Wilders, and the Italian Lega Nord Secretary Matteo Salvini, referred to “Brussels’ politically correct élite.” In this case PC was used as an “epithet”. This rhetorical tool is utilized when an adjective accompanies a name to describe someone’s most important quality (e.g. Ivan the Terrible). The label indicated that the European Union is led by elites who have one single, specific concern: political correctness.

By reducing PC to an elite concern, politicians suggest three things. First, that political correctness is irrelevant to the actual social and political realities. Second, that the power holders are incapable of addressing the real problems of societies. Citizens of Europe are “tired of governments that don’t listen to them and of Brussels imposing decisions that are not put under scrutiny” — argued Geert Wilders for instance. The third implication is that politicians who attack PC side with the people.

FIXATION VS NORMALITY

Critics of PC also use terms associated with extreme behavior (“obsession”, “excess”) to describe those who are concerned with being PC. Radical right parties in Europe frequently talk about the media’s “obsession with political correctness”. According to Donald Trump, his political rivals “have put political correctness above common sense, above your safety and above all else.” Following the same logic, critics of PC also accuse it of defending deviant behavior. Russia’s powerful President, Vladimir Putin said: “The excesses of political correctness are leading to the point where people are talking seriously about registering parties whose goal is legalizing the propaganda of paedophilia.”

These statements suggest that PC could occupy people’s mind, leading them to tolerate ideas and actions that are irrational, harmful, and abnormal. Putin’s statement discredits the actual causes of PC — including the rejection of discrimination based on sexual orientation — through associating them with sexual deviance. The implication is that tolerance of gay marriage, for instance, is just one step away from being understanding of paedophila.

If the concern with PC is described as a symptom of a mental disorder that imposes a fundamental threat to the life and values of societies, the anti-PC agenda can be represented as a protective measure to restore normality and the status quo. For example, on such grounds, Putin called for the “defense of traditional values”.

INTIMIDATION VS COURAGE

Possibly the most common way of attacking political correctness, is to label it “tyrannical”. Covert speech strategies may also support this construction. For instance, anti-PC politicians often utilize adjectives for fear (including “afraid”, “frightened”, “scared”, “terrified”) to describe how PC affects the behavior and feelings of people. The former leader of the UK Independence Party, Nigel Farage claimed: “I think actually what’s been happening with this whole politically correct agenda is lots of decent ordinary people are losing their jobs and paying the price for us being terrified of causing offence.” Suggesting that the British are “terrified” because of political correctness, Farage urged his listeners to think of PC in terms of intimidation.

At the same time, the fearsome vocabulary provides a background for anti-PC populists to present themselves as “brave” and “courageous” “saviors” of their “victimized” societies. The next quote by Nigel Farage exemplifies this trend: “I think the people see us as actually standing up and saying what we think, not being constrained or scared by political correctness.” In a similar fashion, Geert Wilders declared: “I will not allow anyone to shut me up.”

CENSORSHIP VS FREEDOM OF SPEECH

As the previous quotes had illustrated, the tyrannical image of PC is also widely reinforced by the suggestion that the principle violates people’s right to free speech. Hungary’s Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán identified PC as a “muzzle” and as “captivity”. These metaphors present PC as a form of censorship that is enforced through coercion. “Muzzle” triggers frightening associations of being silenced by force, through the degradation of humanity (horses and dogs wear muzzles). The term “captivity” also indicates that PC physically limits people’s right to free speech. Such tropes trigger bodily discomfort and evoke the immediate urge to resist by the listeners.

If PC is constructed as censorship, the anti-PC agenda can fascinate people by offering them the liberating feeling of regaining their right to speak “freely”. Accordingly, Orbán argued that with Trump’s victory in the US, Western civilization “can return to true democracy, to honest talk, away from the crippling restraints of political correctness.” While implying again through a metaphor (“crippling restraints”) that PC involves coercion, Orbán attempted to enhance the appeal of the anti-PC agenda.

Much like the adjectives used for fear, the censorship-topos allows speakers to position themselves as “outspoken”, “authentic”, and “brave” for rejecting PC speech. If political correctness is defined as “tyranny”, then offensive, derogatory, or discriminatory rhetoric can be presented as “heroic”. “Not politically correct, but I don’t care” — commented Donald Trump on his plan to ban Muslims from the US.

DECEPTION VS HONESTY

Within the framework of the censorship-narrative, PC is also presented as deception. On such occasions, the implication is that PC forces people to live in an artificial world in which actual problems become taboo. A recent article by the leader of the Alternative for Germany party, Frauke Petry, is a typical example of this speech strategy. Similarly to other populist radical right figures in Europe, Petry cheered Trump’s presidential victory in the US for marking “the end of political correctness”. She justified her enthusiasm by identifying PC as a “euphemism”, the “distortion of reality”, and the “cover-up of problems” of which people are “sick of”.

By constructing political correctness as a deception and a lie, politicians like Petry can picture their agenda and themselves as “genuine”, “sincere”, and “authentic”. As Geert Wilders put it: “It is my duty, to talk about the problems even when the politically correct elite prefers not to mention them.” As we have seen before, Hungary’s Orbán also lures his public with “honest talk”.

In many contexts, political correctness can indeed counter and discourage deep-seated thinking and speech patterns in society. The current rise of anti-PC politicians both signals and fosters this trend, with important implications. Through portraying PC as something forced down the throats of societies, anti-PC politicians not only discredit an expression but also undermine the idea behind it. In principle, political correctness intends to contribute to greater social equality and fairness. Yet, this notion of PC has become obscure in contemporary political discussions. In this situation, it is harder than ever for the idea of PC to win hearts and minds. However, one thing seems to be apparent: those who would like to stick with the ideals of political correctness, should consider giving a new name to their cause. Political correctness might not be what they mean anymore.

This post originally appeared on Talk Decoded, a blog about the power of language in politics.

Dr. Anna Szilagyi describes how politicians including Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump frame the term political correctness as an attack on ordinary people.

DownloadRead More