In late November 2017 a Bachama militia attacked a series of Fulani villages in northern Adamawa state in eastern Nigeria, killing around 80 people. Most of the dead were women and young children. The graphic images of mutilated bodies from the attack were shared widely on social media, and leaders on both sides employed incendiary rhetoric, either vowing revenge or blaming the victims for the attack. In early December, a botched police operation in an adjacent Fulani village led to rumors of retaliation and a mass exodus from the nearby town. A few days later, eight Bachama villages were attacked by Fulani herders. The Nigerian air force intervened with a jet and attack helicopters, killing 86 people and destroying 3,000 houses.1

Between 2015 and 2019, conflicts between farmers and herders in central and northern Nigeria such as the one described above have claimed over 8,000 lives, with victims and perpetrators on both sides.2 While these conflicts are rooted in highly local disagreements over access to natural resources, dangerous speech on social media has increasingly re-framed them as an existential threat to the entire nation, drawing more people into the conflict and deepening religious and ethnic divisions.

Herders in Nigeria are mostly Fulani, a large cultural community that stretches across West Africa. Almost all Fulani are Muslim, but beyond that are divided by complicated linguistic and cultural subgroups, a multitude of castes, and colonial-era borders. While Fulani are often associated with nomadic herding, and indeed pastoralism has a special reverence among many Fulani, the vast majority are settled and practice some degree of agriculture. On the other hand, farmers in central Nigeria are mostly, but not exclusively, Christian, and belong to dozens of smaller ethno-linguistic communities. Historically, peoples who herded livestock and farmed crops in central and northern Nigeria have coexisted relatively peacefully, with nomadic herders exchanging animal products with farmers for grain or access to pasture.3

However, as rainfall has become more erratic in recent decades, herders have brought their livestock further south, competing with farming communities for access to land and water. At the same time, land tenure agreements have eroded and the mechanisms that previously handled conflicts have been undermined. A decade of fierce communal conflict in the 2000s, the growth of criminal cattle rustling networks, the proliferation of light arms, and the rise of the terrorist group Boko Haram have normalized violence.4 In the last few years, states in the center of the country have instituted bans on open grazing of livestock, undermining a key aspect of herder livelihood and pushing herders into neighboring states, where the influxes have also escalated tensions. In this context, local altercations over land have escalated and militias are increasingly mobilized, leading to intensifying clashes and retaliatory violence. Perpetrators on all sides largely enjoy impunity, and victims rarely receive any kind of justice.5

While online speech is rarely implicated in initial violent incidents, social media platforms increasingly play host to dangerous speech after an act of violence. As news of an attack spreads, it becomes imbued with toxic narratives of alleged Fulani genocidal jihad, or a centuries-old effort by Christians to undermine Islam in Nigeria, linking horrific yet locally rooted violence to larger existential questions about the nation’s identity. These narratives are constructed through a series of messages and tropes that reflect the social and historical context of Nigeria.

One of the two prominent narratives that have developed portrays Fulani as a monolithic group of aggressors. The label “killer herdsmen” has taken hold in the popular press and is used in many headlines whenever Fulani are involved, even as victims.6 The images that many news websites use for articles also contributes to this narrative.

For example, this photo from the Central African Republic, showing Fulani as aggressors, is frequently used in Nigerian news articles – even though the building in the background shows the widely recognized logo of Orange, a French cell phone company that does not operate in Nigeria.7

Another gruesome image of dead bodies scattered on the road alongside a bus has been circulating for at least eight years, accompanied by a series of false rumors about herders ambushing highways.8

Over the last few years violent incidents implicating Fulani herders have been inevitably followed by social media posts which allege a unified and coordinated “Fulani jihad” harking back to the establishment of the Sokoto Caliphate in the 19th century by Usman Dan Fodio. These posts, such as the one shown here, re-present the establishment of the Sokoto Caliphate as an ethnic jihad launched by the Fulani.9 Building on this flawed understanding of Nigerian history, they argue that contemporary violence is actually part of a centuries old effort to forcibly convert Nigeria to Islam. This simplistic and inaccurate narrative builds on one-sided readings of Nigerian history, mischaracterizes the current conflicts, and obscures the fact that there is significant tension within the Fulani community and that Fulani are themselves victims of cattle rustlers and ethnic militias. Furthermore, it justifies any violence against Fulani as against an aggressive enemy while also concealing the structural causes of the conflict. These misleading images and headlines simplify a complicated and nuanced situation with dangerous stereotypes that only reinforce preconceived notions that contribute to conflict.

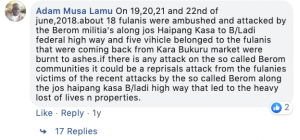

On the other side, a cursory search of Facebook following attacks by suspected herders reveals a range of justificatory mechanisms, condoning violence and reducing in-group pressure for tolerance and understanding.10 One example comes from after attacks by suspected Fulani herders in Barkin Ladi in June of 2018 that claimed over 200 lives. According to a Facebook post which laid out six incidents of cattle rustling in early June, a “series of unprovoked attacks by Birom’s tribes men on Fulanis across Plateau state, incurred the wrath of the herdsmen to take a deadly reprisals attacks across Barikin Ladi LGA of Plateau state that resulted to wiping off of 11 Birom’s villages across the region.” This line was picked up by Fulani and Muslim partisans on Facebook, as in the accompanying screen shot taken from the comments on gruesome photos of dead Christians publicly posted by a Christian man to his Facebook page days after the attack.

On the other side, a cursory search of Facebook following attacks by suspected herders reveals a range of justificatory mechanisms, condoning violence and reducing in-group pressure for tolerance and understanding.10 One example comes from after attacks by suspected Fulani herders in Barkin Ladi in June of 2018 that claimed over 200 lives. According to a Facebook post which laid out six incidents of cattle rustling in early June, a “series of unprovoked attacks by Birom’s tribes men on Fulanis across Plateau state, incurred the wrath of the herdsmen to take a deadly reprisals attacks across Barikin Ladi LGA of Plateau state that resulted to wiping off of 11 Birom’s villages across the region.” This line was picked up by Fulani and Muslim partisans on Facebook, as in the accompanying screen shot taken from the comments on gruesome photos of dead Christians publicly posted by a Christian man to his Facebook page days after the attack.

In some places these messages have created a “chosen trauma,” a term coined by social psychologist Vamik Volkan whereby a memory of group suffering, loss, helplessness, and humiliation in a conflict with a neighboring group becomes an important keystone moment in their identity, and in some cases a justification for future violence.11 Sharing images and reigniting the memory of previous victimization can serve as justification for future violence. The gruesome images from the November 2017 attack in Adamawa state are still brought as evidence of Fulani victimization. Indeed, the images were re-posted as the “pinned item” almost two years after the attack on a Facebook page with over 15,000 followers which traffics in one-sided highly partisan content alleging the Fulani are the victims of genocide.

In some places these messages have created a “chosen trauma,” a term coined by social psychologist Vamik Volkan whereby a memory of group suffering, loss, helplessness, and humiliation in a conflict with a neighboring group becomes an important keystone moment in their identity, and in some cases a justification for future violence.11 Sharing images and reigniting the memory of previous victimization can serve as justification for future violence. The gruesome images from the November 2017 attack in Adamawa state are still brought as evidence of Fulani victimization. Indeed, the images were re-posted as the “pinned item” almost two years after the attack on a Facebook page with over 15,000 followers which traffics in one-sided highly partisan content alleging the Fulani are the victims of genocide.

The demonization of Fulani plays into larger narratives of Islamic victimization in independent Nigeria and risks enmeshing the country in dynamics similar to other parts of the Sahel, – the area stretching across Africa between the Sahara desert to the north and the forest to the south – where a small subset of Fulani have joined armed groups in response to perceived victimization at the hands of the state and other groups.12 Since 2012, grievances among a subgroup of Fulani herders in Mali have morphed from isolated attacks against local Fulani elites to affiliation with regional jihadist groups and large-scale attacks on the state. In response, farming communities – who in most of the Sahel are also Muslim – have organized their own militias, ostensibly for their own protection, but who have also been implicated in attacks described by the International Crisis Group as “ethnic cleansing.”13 Meanwhile, governments increasingly ascribe collective guilt to all Fulani people and have pursued collective punishment in some place, which has become a recruiting tool for regional jihadist groups.14 News of massacres of Fulani in Mali and Burkina Faso is shared on social media across the Sahel, fueling a growing sense of marginalization and victimization.

However, while the structural conditions that have given rise to communal conflict involving herders and farmers are similar across the Sahel, the risk that they unite and pose a legitimate threat to the secular states of the region – even with the corrosive influence of dangerous speech on social media – is low. Fulani people are divided by a multitude of languages, castes, and socio-economic status, and in my experience the vast majority are invested in the current order.15 However, as the livelihood of an important segment of their society is undermined, and they are collectively blamed for the actions of a minority, individuals and communities might seek help fighting back from other places in the Sahel. Understanding and addressing the root causes of conflict between herders and farmers in Nigeria is imperative to stopping the cycle of violence and further radicalization.

James Courtright is a graduate student at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. Before pursuing a Master’s degree, he was based in Senegal for several years, first as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Kolda and then as a freelance journalist in Dakar.

Footnotes

- “Harvest of Death: Three Years of Bloody Clashes Between Farmers and Herders in Nigeria” (Abuja, Nigeria: Amnesty International, December 17, 2018), 25–27, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr44/9503/2018/en/

- Reliable numbers are extremely difficult to come by as all sides in the conflicts seek to maximize the killings by their opponents and minimize their own attacks. This figure comes from Hilary Matfess, “What Explains the Rise of Communal Violence in Mali, Nigeria and Ethiopia?,” World Politics Review, September 11, 2019, https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/28182/what-explains-the-rise-of-communal-violence-in-mali-nigeria-and-ethiopia.

- Catherine Ver Eecke, “Pulaaku: Adamawa Fulbe Identity and Its Transformations” (Philadelphia, USA, University of Pennsylvania, 1988); Aliya A. Idrees and Yakubu A. Ochefu, Studies in the History of the Central Nigeria Area Vol. 1 (Lagos, Nigeria, 2002).

- Scholars such as Jana Krause argue that “farmer-herder” conflicts are best understood as communal conflict with “strong political dimension that interacts with state structures and elite politics” in addition to the aforementioned climactic factors. Personal communication with the author, 2020.

- “Stopping Nigeria’s Spiraling Farmer-Herder Violence” (Brussels, Belgium: International Crisis Group, July 2018), i.

- Cletus Famous Nwankwo et al., “Farmer-Herder Conflict: The Politics of Media Discourse in Nigeria,” Ponte 76, no. 1 (January 2020); Innocent Chiluwa and Isioma Chiluwa, “‘Deadlier than Boko Haram’: Representations of the Nigerian Herder–Farmer Conflict in the Local and Foreign Press,” Media, War & Conflict, February 7, 2020.

- David Ajikobi, “Deadly Nigeria Conflict? No, Pic Was Taken in Central African Republic,” Africa Check, March 20, 2018, https://africacheck.org/spot-check/deadly-nigeria-conflict-no-pic-was-taken-in-central-african-republic/.

- David Ajikobi, “Viral Picture of ‘Fulani Massacre’ at Least 8 Years Old,” Africa Check, February 10, 2018, https://africacheck.org/spot-check/viral-picture-fulani-massacre-least-8-years-old/.

- The historiography of the Sokoto Caliphate is contentious and, in many places, still based on uncritical readings of fundamentally flawed colonial sources. Yusufu Balla Usman and others have shown how ethnicity was written into western understandings of the Caliphate by European “experts” and has come to dominate popular understandings despite being inaccurate. Yusufu Bala Usman, Beyond Fairy Tales: Selected Historical Writings of Yusufu Bala Usman (Zaria, Nigeria: Abdullahi Smith Centre for Historical Research, 2006).

- Jonathan Leader Maynard, “Rethinking the Role of Ideology in Mass Atrocities,” Terrorism and Political Violence 26, no. 5 (February 2014): 14–15.

- Vamik D. Volkan, “Transgenerational Transmissions and Chosen Traumas: An Aspect of Large-Group Identity,” Group Analysis 34, no. 1 (March 1, 2001): 79–97.

- Modibo Chaly Cissé, “Understanding Fulani Perspectives on the Sahel Crisis – Africa Center,” Understanding Fulani Perspectives on the Sahel Crisis, April 22, 2020, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/understanding-fulani-perspectives-sahel-crisis/.

- Jean-Hervé Jezequel, “Centre Du Mali : Enrayer Le Nettoyage Ethnique,” Crisis Group, March 25, 2019, https://www.crisisgroup.org/fr/africa/sahel/mali/centre-du-mali-enrayer-le-nettoyage-ethnique.

- Corinne Dufka, “‘We Used to Be Brothers’: Self-Defense Group Abuses in Central Mali” (Human Rights Watch, December 2018).

- See also Modibo Chaly Cissé, “Understanding Fulani Perspectives on the Sahel Crisis,” Understanding Fulani Perspectives on the Sahel Crisis, April 22, 2020, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/understanding-fulani-perspectives-sahel-crisis/.